Pisidian Antioch (Antiochia in Pisidia)

(Antiocheia)

/ By Josh

Cost: 10TL

(Museum Card Accepted, the Yalvaç Museum, where artifacts are displayed, is free)

Great for: Roman History, Christian History, Seljuk History, Ancient Church

In a country full of ancient sites, Pisidian Antioch stands out as a place of unique history. While the city was not listed among the great cities of the region it was grand, wealthy, and came to play a unique role in history, its later importance and fame owing more to the important events that took place within its walls than its might or influence. While the city was thoroughly destroyed in the 11th and 12th centuries, there is no mistaking the grand aqueducts, thick walls, ornate archways, and vast plazas, for anything other than a great city.

Subscribe to The Art of Wayfaring

History of Antioch in Pisidia

According to tradition, the city of Pisidian Antioch (also known as Antioch in Pisidia, Antiocheia, and because it was sometimes part of the province of Phrygia, Antioch of Phrygia) was founded by Seleucus I Nicator sometime in the 4rd century BC and named for his father Antiochus (he went on to name 16 cities after his father, including Antakya). Another theory, perhaps better supported by historical record is that the city was founded by the son of Seleucus, who was also named Antiochus, and in turn named his son Antiochus.

While tradition points to a 4rd century BC founding of the city, the presence of the cult of the god Men, indicates the settlement must date back earlier yet.

The Selucids poured money into Antiocheia, bringing in settlers and building strong walls to protect it against the unruly Galatians, a Celtic people who had immigrated from Europe and settled in the region.

After two centuries of Seleucid rule, control of the region passed to the expanding Romans, who enacted a similar policy in the city. The Romans spent liberally in the city on grand building projects, settled retired legionnaires here, and used it as a bulwark against unruly neighbours, only in this case it was to defend against the raiders and bandit kings of Pisidia’s rugged mountains (see the history of the Ancient City of Kremna).

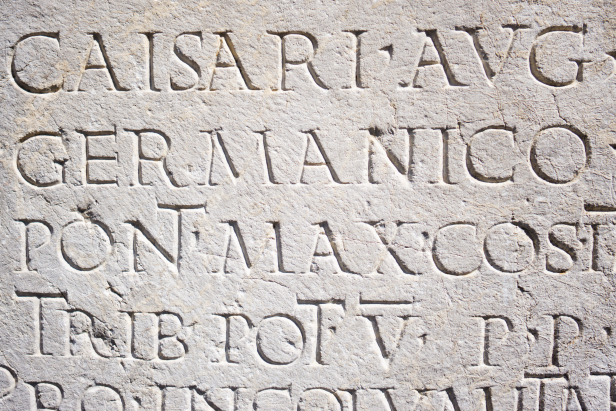

Settling Roman legionnaires in Antioch led to an incredible Romanization and Latinization of the city in what was otherwise a strongly Hellenized and Greek speaking region. The city’s major buildings honored Roman Emperors, inscriptions were written in Latin, and the city was honoured with a copy of The Deeds of the Divine Augusts in Latin (Greek copies were found in nearby Apollonia [Uluborlu] and Ancyra [Ankara]). It wasn’t until the 3rd century that Latin finally gave way to Greek.

Early Christian History of Pisidian Antioch

The city of Antiocheia reached the height of its fame with the beginnings of Christianity when St Paul and his companions came to the city to preach the Christian Faith to the Jews that lived in the city. He would visit the city on all of his three recorded journeys, initially preaching in the Jewish synagogue, before sharing his message with the general populace of the city.

Paul arrived in Pisidian Antioch from Cyprus, passing through Antalya and Perge. St Paul’s companion on his first Journey was Barnabas, a native of Cyprus. While in Cyprus Ss. Paul and Barnabas met the Roman Proconsul named Sergius Paulus. After meeting with Sergius Paulus, who converted to Christianity, Ss. Paul and Barnabas continued on to the city of Pisidian Antioch via what is now Antalya and Perge. It is thought that they may have chosen Pisidian Antioch as it was the home of Sergius Paulus. A number of inscriptions have been found bearing his name, one of which bearing the Latin version of the name (Sergii Paulo) can be see in the Yalvaç Museum.

For more about the Biblical account of Paul in Pisidian Antioch see Acts 13, 14 and 2 Timothy 3:11

Following the Christianization of the Roman Empire the city became an important religious center with large churches being built at a very early period in the city.

The Decline, Fall, and Establishment of Yalvaç

Following the decline of the Romans and the Byzantines the city fell into disrepair. in the early 8th century the growing power of the Ummayads, one of the early Islamic Empires, had made serious inroads into what is now Turkey, and in 713 Pisidian Antioch was attacked by al-abbas ibn al-Walid. While the territory would continue to be ruled by the Byzantines, the beauty and power of the city had ended.

The ultimate ruin of Antioch in Pisidia would come in 1176 when the Byzantines lost a decisive Battle to the Seljuk Turks. The Seljuks, rather than settling in the ruins of the city, or building a new city atop the ruins, elected to use the old city as a source of masonry and dismantled the ancient buildings, splitting the larger stones into smaller, workable sizes to build the new town of Yalvaç a short distance below.

Why Visit?

Pisidian Antioch Ancient City

Entering the city through the museum entrance, you will find yourself passing below some of the larger remains of the city walls and walking up towards the city’s Western Gate. The gate was rebuilt in the 3rd century as a triumphal arch, with beautifully carved figures of mermaids, angels, bulls, and shields, set around the three arches of the gateway. While the gate is now in ruins, you can see the reliefs set around the base of the gateway.

Turning right just beyond the gate, you will begin walking up the Decimus Maximus, one of the city’s main streets, connecting the Western Gate to Tiberius Square and the colossal Temple of Augustus. The city’s theater is on the left side of the road. The theater dates back to the founding of the city in the 3rd century BC but was greatly expanded in the beginning of the 4th century AD by the Romans. While the theater doesn’t look particularly impressive today, it was actually one of the largest in the region, nearly 100 meters wide, built over the Decimus Maximus street, and able to hold approximately 12000 spectators. The quality stones of the theater were heavily ransacked by the Seljuks who used the convenient stones to build the new city of Yalvaç below.

Turning left off of the Decimus Maximus onto the Cardio Maximus, the other main thoroughfare of Antioch, the remains of a large three-aisled church, referred to as the Central Church, have been uncovered. The original survey of the site suggested a small, Latin style church, though later excavations revealed a much larger church built in the Orthodox style dated to the 4th or 5th centuries. Most interesting to the Christian visitors is the floor found below the church, believed to belong to a synagogue of the city’s large Jewish population, and possibly the site of St Paul’s sermon recorded in Acts 13:16.

Signage at the church of St Paul (Great Basilica) also makes the same claim of being built atop a synagogue. Whether there is a mistake here or both were built on the remains of an older synagogue is unclear.

Across from the Central Church is the impressive Square of Tiberius and the heart of the city of Antioch. The large square was flanked by numerous shops and, to the east an ornate Propylon, or monumental gateway of Corinthian pillars, set above the Square of Tiberius on a flight of steps. The gate was built as the monumental entrance to the sanctuary of Augustus. The Propylon also housed the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, or The Deeds of the Divine Augustus in Latin. Greek copies of the text have been found in the nearby city of Apollonia (Uluborlu) and at the Temple of Augustus in Ankara.

Through the monumental gate is the sanctuary of Augustus, Emperor of Rome. The Sanctuary was built at the highest point in the city on a site that was likely used in previous eras as a temple to the moon-god Men, or mother goddess Cybele. The site consists of a wide-open plaza carved into the bedrock, centered on a four columned prostylos style temple built on a high platform. The temple was surrounded by a two storeyed portico consisting of a grand sweeping curve cut into the bedrock behind the temple itself, as well as wings on the right and left of the temple, forming an enclosed holy space, entered by the gateway from the Square of Tiberius.

Today the carved bedrock still shows the shape of the portico with rectangular cuts in the rock where beams would have connected the pillared face of the portico to the rock wall behind. Most of the pillars, architectural elements and rubble have been removed or laid out to give a sense of the grandness and richness of this central holy place dedicated to the cult of the god-emperor Augustus.

Subscribe to The Art of Wayfaring

Continuing northward along the Cardio Maximus you will come to triple aisled church. The church was more recently uncovered and not present on some of the older maps of Antiochia in Pisidia.

Further along the Cardio Maximus widens, almost becoming a plaza before terminating at the Nymphaeum, or fountain-shine to the nymphs. The Nymphaeum of Antioch of Pisidia served as a water storage tank from which water brought in from the mountains to the north could be redistributed to other parts of the city. While little remains of the fountain apart from the large foundation stones and bottom of the pools and tanks, there would have once been a beautiful façade of pillars and statuary intermingled with water flowing out into pools.

From here you can see the aqueducts that once brought water from the Sultan Mountains in the north into the city. Even in their current state of ruin they are impressive as they snake along the crest of low hills that lie between the city ruins and the water source to the north.

(Note that the aqueduct is outside of the museum grounds and will need to be visited separately. See Getting There for more details below.)

Following a dirt track westward (to the left) from the Nymphaeum there are the ruins of a large basilica styled church, believed to have been built around the 6th century. Like many of the buildings in Pisidian Antioch, this northern church has been reduced to ruins with the apse forming the best-preserved portion of the church.

Immediately beyond the church ruins are the much more impressive ruins of a large, vaulted building usually referred to as a Roman Bath. While these ruins are often described as a bath, they have not been fully excavated and it still isn’t certain what function this building once served. Unfortunately, access to these ruins is limited and fenced off.

Between the supposed Roman Baths and the museum entrance is the Great Basilica, also known as the Church of St Paul. The church structure was evidently built and expanded in stages, with different levels to accommodate the slope that it was built on. A mosaic found in the floor of the Church of St Paul makes mention of Archbishop Optimus, who is recorded as having attended the First Church Council of Constantinople in 381, giving us an approximate date for the original building of the church sometime before 381. According to the signage at the church, a synagogue was also found beneath the church structure. Whether the Great Basilica and the Central Church were both built upon 1st century synagogues or there is some mistake here is unclear.

Today the central apse sits sunken a few meters lower than the floor of the nave and a makeshift altar has been placed for use by visitors.

The Town of Yalvaç

Museum

The Yalvaç Museum is home to a number of interesting finds from the ruins of Pisidian Antioch and the surrounding area. The museum covers history from the prehistoric on to the 19th century with fossils, statuary, christian reliquaries, and medieval weapons on display. While the unusually muscular chihuahua may be the most eye catching, the tablets of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, or The Deeds of the Divine Augustus, are some of the most important finds on display here. Among the items on display there is a small vase-shaped vessel of gold which was presented as a trophy to a gladiator of the Pisidian Antioch who overcame a crocodile in the arena. Also of particular interest is the stone inscribed with the name of Sergius Paulus, the above mentioned early convert to Christianity, and proconsul of Cyprus.

Traces of Antioch in Yalvaç

Following the fall of Antiochia in Pisidia to the Seljuks in 1167, the old marble structures were dismantled, the massive ancient blocks broken up and used to build the new Turkish settlement of Yalvaç.

One of the best places to see these repurposed blocks is in the walls of the Devlethan Mosque in the center of Yalvaç. Here you can see various architectural elements including inscriptions, and even the faint remains of a cross. The mosque is thought to date to the 15th or 16th century, implying that the locals continued using the old city as a quarry for many centuries. While the mosque is relatively uninteresting, the interior domes are rather strange in that they are ovals rather than proper circles.

(mosqu int)

Across the street from the Devlethan Mosque is a massive plain tree, dated back to the original Turkish conquest of the city, making it around 800 years old. The stunning tree provides shade for the Çınar Altı (literally “Beneath the Plain Tree”) square where locals gather to drink tea and socialize.

How To Get There

Car

To reach the aqueduct continue up the paved road past the open-air museum and continue upwards to the left on a dirt track. The road has been blocked with piled earth so you will need to park here (if you are driving) and continue the next 100 meters or so on foot. There is a lower road that doesn’t quite reach the aqueduct and it is very narrow and muddy; it’s easy to get a car stuck here.

For more about car rental and driving in Turkey make sure to read our full drivers guide.

Public Transport

While somewhat distant from other major cities, Yalvaç is well connected for those traveling by bus. There is regular service to the Yalvaç Bus Station from the cities of İsparta and Afyon, as well as service from the town of Aksehir.

Where To Stay

There’s a surprising number of hotels to choose from in Yalvaç, ranging from good quality mid-range priced hotels to cheap dives if you’re looking to save money.

Other Tips

Planning on visiting Yalvaç and Pisidian Antioch? Make sure to check out what other sights are in the region!

Subscribe to The Art of Wayfaring

Have any tips or info to add? Spot any mistakes? We’d love to hear about it.